|

As the Mangalyaan closes in on Mars, there is palpable excitement among Indian as well as the world space community. Until now, less than half of the nearly fifty missions sent to Mars (or its moons Phobos and Deimos) by various countries have been successful and no country has ever reached Mars on the first try. If successful, ISRO would become the fourth space agency to reach Mars, after the Soviets, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the European Space Agency (ESA).[i] With a successful launch and injection into the interplanetary orbit, India has already joined the select group of countries that have demonstrated ability for inter planetary travel. It now faces the critical test of firing the spacecraft’s onboard rocket to change its orbital path and slow itself sufficiently to be captured by Mars’ gravity. There is only one chance to get that right or the spacecraft will continue to go on past Mars, never to get back.

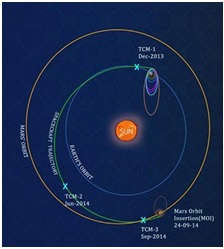

Mangalyaan was successfully launched on November 5, 2013 aboard PSLV C25 (XL version).[ii] The timing of launch was crucial to take advantage of the opportunity that comes once in 26 months when the geometry of the sun, Mars and Earth is perfect for a fuel-saving Hohmann transfer orbit.[iii] It was initially put into Earth’s orbit where its liquid fuel engine of 440 N (Newton) thrust was used for six orbit-raising manoeuvres to gradually build up its orbital velocity. On reaching the desired orbit, on 30 Nov 13, it was imparted an additional velocity, through the seventh burn of the on-board 440N propulsion system, that enabled it to achieve the necessary escape velocity to break free from Earth's gravitational pull for a successful Trans-Martian Insertion (TMI). It has since followed a heliocentric elliptical trajectory[iv] around the Sun for its nearly yearlong transit to Mars. Such manoeuvres are very intricate and require high degree of computation skills and control. The Mangalyaan also has eight 22 N thrusters for attitude control or orientation that were used along with the main booster during the TMI and subsequently for three of the four trajectory correction manoeuvres (TCMs), required to fine-tune the course toward Mars. (One TCM was skipped as the craft was already on the desired path).

Source: ISRO

The spacecraft has been monitored and controlled throughout from the Spacecraft Control Centre at ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) in Bangalore. Till April, 18 metre dish antennae at the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) at Byalalu were used for communication with the craft. Since then the larger 32-metre antenna system, whose power has been augmented from 2kW (used for the Chandrayaan mission) to 20 kW, to cater to the larger distances of the Mars mission, have been used. Support during the non-visible period of ISRO's network has been provided by NASA’s Deep Space Network.

Check up of the onboard medium gain antenna that would be used for communicating with the Earth control during the critical Mars Orbit Insertion (MOI) manoeuvre was carried out in early August. Ground controllers have to cater to the communication delay with the spacecraft that presently is more than 20 minutes one way. Therefore, the spacecraft has been built with a reasonable amount of autonomy, which would also come into play during the MOI as the spacecraft would be eclipsed by Mars during most part of the manoeuvre. During the long flight, the spacecraft also periodically activated its five instruments for regular checkups to ensure all instruments remain functional. These indigenous instruments would take images of the planet and study its atmosphere. While all has progressed well, the next crucial step is the restart of the 440N propulsion system and its ability to perform optimally after being idle for almost 300 days. On the successful completion of MOI, the Mangalyaan would be in a highly elliptical orbit around Mars with the closest point of 377 km and the farthest being 80,000 km.

India’s Mars mission has been in the news consistently for a variety of reasons. The critics point out that a poor country like India should not have spent money on a mission which has few tangible benefits unlike the other ISRO missions. They also argue that most of Mars Orbiter Mission’s (MOM) objectives have already been achieved by previous missions and that there is nothing new to show for the large amount of money spent. Even the former ISRO Chief, G Madhavan Nair, has pointed out that the planned elliptical orbit of 377km X 80000 kms is not suitable for any meaningful study. According to him, GSLV was the vehicle identified because it could take a respectable satellite of nearly 1,800 kg. “This could have provided more than a dozen instruments on board and the spacecraft would have been placed in a near circular orbit for a meaningful remote sensing mission of Mars.”[v]

The ISRO chief, K Radhakrishnan, has defended MOM by acknowledging that the primary objective of the mission is to develop and test technologies necessary for long inter-planetary missions and that scientific exploration is only secondary. Others have highlighted the low cost of the mission. The Prime Minister famously quoted the cost of the mission to be lower than that of making the Hollywood movie ‘Gravity’. This has mainly been made possible because of a number of reasons which include the low cost of human resource in India. Also, the development schedule was short and unlike the other missions which involved building of many models, ISRO scientists built the final flight model right from the start, depending mainly on simulation testing on computers. They were of course fortunate to have data from previous missions to work upon. The use of the existing PSLV launch platform also contributed to the mission’s cost effectiveness. Also, ISRO resorts to the modular concept of using similar components and systems across its different projects that further keep costs down. Communication and navigation support provided by NASA’s Deep Space Network was also beneficial.

Besides the intangible effect of spreading more scientific awareness in the country and boost to national pride, the success of the MOM would also further help position India as a budget player in the expanding commercial market in satellite launches and space exploration. This would in turn have a multiplier effect on the private industry which has made more than two thirds of the parts for both the probe and the rocket for the mission.[vi]

Notwithstanding the critique, the MOM has already given much for India to cheer about. If the MOI goes as planned, it will indeed be a proud day for India. The successful flight of the indigenous cryogenic upper stage on the GSLV in January 2014 has encouraged talks of a follow up mission with a greater scientific payload during future launch windows.

Views expressed are personal.

|